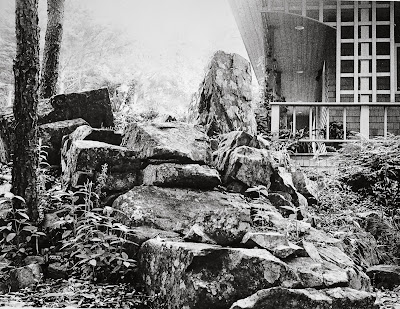

I was a hardscape stonemason for twenty years, building walkways, terraces, and dry-laid stonewalls. My favorite task was building natural-looking ledges to integrate a new home perched awkwardly on a bulldozed dirt mound, back down into the natural rhythms of nature. I would first conceive what I wanted to build, gather likely-looking stones with my backhoe, and load them in my dump truck. Inevitably, however, the stones rebelled on the trip back to the job site, shapeshifting into forms that stymied my original plan of action.

I had to start all over again. What is it with those rocks? I agree with Mark Peter Keane, who worked with stone masters in Kyoto, Japan, for two decades. He always claimed that rocks had a mind of their own. We also understand that setting the first stone is the most important because it determines the path of all who follow.

That's where the rubber meets the road.

After the first stone is set, Keane explains,“From here on, the placement of the other stones will follow the precedent of the first one. The ancient nobles wrote … ‘follow the request of the stone.’ … because for them the stone was animate. It had desires, natural dispositions, requests, the fulfillment of which was essential.1

Indeed, I discovered by trial and error, I had no choice but to honor Keane’s ancient mentors. If I tried to think through which piece of ledge should go next, it would stand out like a sore thumb. If I tried to measure which rock should go in the next in a wall, it would refuse to fit.

Inevitably, whenever I tried to think myself through the day, things went haywire. Conversely, when I wasn't thinking, I often had magical days when rocks fit perfectly and looked fabulous.

We've all experienced it: being wholly absorbed in the activity at hand, being so involved that we lose our sense of time or even our sense of self. This state of being is what folks describe when they say they're in the zone or groove.

In his ground-breaking work on creativity, Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi2 called this state of being "flow," describing it as being totally focused, "completely involved in an activity for its own sake. The ego falls away. Time flies. Every action, movement, and thought follows inevitably from the previous one, like playing jazz."

We’ve all felt it: "Talking to a friend, reading to a child, playing with a pet, or mowing the lawn can each produce flow, provided you find the challenge in what you are doing and then focus on doing it as best you can."3

It's not a conscious process; it's more akin to Eastern spiritual practices, where the core idea is not to force or grasp our way through life but to live spontaneously in harmony with the natural order of the cosmos.

Finding flow is my secret sauce, not just in stonework but in writing. In both pursuits, setting the first piece determines what will follow. Words like rocks don’t dutifully report for duty just because they have been asked; instead, they volunteer when summoned by their comrades who came before.

In closing, I want to poise a larger question, so far left unsaid: Where does our ability to think come from? For most of our existence on earth, humans have believed our thoughts originate from a greater reality outside of ourselves, not from our tiny, three-pound brain.

Maybe it's time to revisit this question because some facts speak for themselves: while cultures rise and fall, stones and stories persist.

xxx

1 Keane, Marc; Keane, Marc Peter. The Art of Setting Stones (p. 105). Stone Bridge Press.

2 1 Csikszentmihalyi, Mihaly (1990). Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience. New York: Harper and Row

3 http://jeanstimmell.blogspot.com/2021/11/achieving-flow.html

No comments:

Post a Comment